One of the most revolutionary things I have encountered in these recent studies of Luke is the way these commentators, and especially Sarah, interpret Christ's parables. Prior to the past few years, I think I had always read the parables with an underlying assumption that 1) the powerful figure in the story (whether a king or a landowner or a judge) was always supposed to represent God, and 2) that the parables were mostly giving us positive examples of how we are to behave. What I've discovered more recently is that 1) very often the powerful character in the story is often actually the "bad guy", the one who acts unjustly to exploit, harm, or exclude others, and 2) that often the parable is presenting with a negative example - i.e. Jesus is illustrating what we shouldn't do, what we need to avoid. The difference comes when you start to look at these passages in their cultural, historical and socio-economic context. If we ask ourselves not just "what do the words on the page say?", but also "what would this have meant to the original hearers?" new meanings start to emerge.

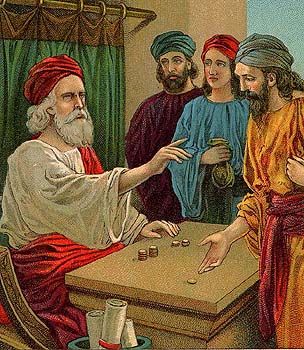

For instance, the "parable of the shrewd manager" in Luke 16 is one that has often stumped believers. We are told of a wealthy landowner's steward who is accused of "wasting" his master's possessions. The landowner threatens to fire him, so the steward calls all his master's debtors and erases the interest portion of their debt in hopes that they'll treat him well after he's out of a job. The strange thing is that the master commends the steward for his dishonest move and Jesus tells us to be like him. At first glance it's hard to see why Jesus would tell us to be like a deceitful servant. Isn't the landowner like God, and aren't we like stewards of God? Why would Jesus encourage us to cheat God?

For instance, the "parable of the shrewd manager" in Luke 16 is one that has often stumped believers. We are told of a wealthy landowner's steward who is accused of "wasting" his master's possessions. The landowner threatens to fire him, so the steward calls all his master's debtors and erases the interest portion of their debt in hopes that they'll treat him well after he's out of a job. The strange thing is that the master commends the steward for his dishonest move and Jesus tells us to be like him. At first glance it's hard to see why Jesus would tell us to be like a deceitful servant. Isn't the landowner like God, and aren't we like stewards of God? Why would Jesus encourage us to cheat God?However, if we place ourselves in the place of a 1st century tenant farmer, like the ones Jesus was likely preaching to, suddenly it's not so clear that the landowner is the "good guy" in the story. In the Hebrew Scriptures God tends to not look to kindly on absentee landlords - his intention seems to be that people should enjoy the fruits of their own labors, not just live off the hard work of others. And the fact that this landowner seemed to be charging his own tenants interest is interesting too. Collecting interest, or usury as it is commonly known in the Old Testament, was forbidden to God's people. This landowner was breaking God's law and exploiting the people by doing this. So what the steward does in reducing the farmer's debts is less and act of injustice towards the landowner, and more an act of restoring justice to the farmers. And the moral of the story that Jesus wraps up with is that we should not love money for money's sake, but should instead use wealth to build relationships. He says you cannot love both God and money - which in context seems a critique more aimed at the landowner who had money, than at the steward who had none and gave away that which he had access to.

So read in this light, this parable suddenly seems to be about economic justice towards those who are being exploited - it's about the proper use of wealth, and how we should use it to help people, not exploit them further.

Or let's look at the "parable of the ten minas" (referred to in other gospels as the "parable of the talents") in Luke 19:11-27. Here we are presented with a harsh and violent ruler who leaves his country to be crowned king by the emperor, but whose citizens also send a delegation to ask that he not be made king because of his cruelty (an obvious reference to the real history of Herod Archelaus from Jesus' childhood). While he is gone he gives a small sum of money to ten servants and tells them to invest it while he's gone. When he returns, he finds that one of the servants has failed to do so. The harsh ruler punishes the servant and then proceeds to execute the other citizens who had opposed his reign in the first place.

Again, this parable is usually interpreted with God as the ruler, and us as the servants. The moral in that interpretation is that we'd better do our best with the gifts God gives us or else we'll suffer the consequences. However, when you look at this passage again through the eyes of justice there are a few disconcerting things about that reading:

1) The ruler commands his servants to collect usury, interest, which again, is forbidden by Jewish law. It is considered unjust exploitation of others.

2) The ruler is described as a "hard man" who gets rich off the efforts of others.

3) The ruler's "moral" is that the rich will get richer and the poor get poorer - something that doesn't really seem to line up with Jesus' teachings that the poor will inherit the kingdom, and that the hungry will be filled.

4) The ruler's response to his enemies is violence. This seems the opposite of Christ's commands to love our enemies.

So what if we are instead supposed to read this story as a negative contrast with the kingdom of God? What if the ruler is actually cast in opposition to the values of Christ's kingdom? In this reading the "hero" is the "unfaithful" servant who refused to take part in an unjust system - who dared to defy the evil king by refusing to break God's law. Perhaps this is why in Matthew's gospel he follows up his version of the story with Christ's parable of the sheep and the goats and his command to take care of the "least of these" (i.e. the hungry, the poor, the sick, and the oppressed). At any rate, it is a whole new way of looking at this passage than I am used to, and yet one that seems to deeply resonate with a gospel of love and justice.

How about one more? In Luke 20:9-19 we are given a parable about tenant farmers whose absentee landlord demands revenue from his vineyards one year after they're planted (despite the fact that it takes vineyards several years to establish their vines and start producing a profit). The farmers respond with violence towards the owner's messengers and eventually end up killing his son. In return, the owner comes and slaughters all the tenants.

As you might guess, I had always been taught to read this passage as an allegory where God is the landowner, and Israel is the violent and rebellious tenants who rejected God's messengers (the prophets) and killed his son. However, looking at this passage in it's scriptural and historical context, we have to ask ourselves whether we should really be so quick to allegorize it. Sure, it could be about Israel and God, but given that when he told the parable Jesus was surrounded by real life absentee landowners (i.e. the Jewish chief priests and elders) and tenant farmers (i.e. the gathered masses from the countryside who were all in Jerusalem for the Passover celebration that week) one can imagine that his hearers would have very likely taken this story at face value - as a story about real life economic injustice and the cycle of violent retribution on both sides. And you can imagine that the common people around Jesus would have been more likely to cheer on the tenant farmers who were fighting to take back their ancestral lands from the wealthy Roman collaborators like the chief priests who had stolen it from them, than they would be to sympathize with the landowner in the story, even if he is supposed to represent God.

So in this light, through the lens of justice, this passage seems to be about the cycle of violence and oppression. Neither the landowner nor the tenants win in the end. The former loses his son and the latter lose their land and their lives. Violence only breeds more violence, and when the oppressed respond to their oppressors with oppression of their own, it only results in more injustice.

But again, this interpretation only comes by reading the scriptures 1) through the lens of justice - asking how these stories either support or contrast with Christ's gospel of good news for the poor, the oppressed, and the broken (cf. Luke 4:18-19); and 2) in light of the historical, socio-economic/religio-political realities of Jesus' day. In other words, it requires not simply reading scripture in a vacuum and assuming that our traditional interpretations (which, more often than not, were formed in a historical and cultural setting very far removed from Jesus' day, and usually without much of an eye towards those contextual issues) are necessarily the ones are automatically the "right" ones and that therefore any alternative takes must be "revisionist".

For me, these new set of lenses has helped the gospels come alive, and so much more makes sense now than it did before. It starts to look more like a unified whole, and Christ's gospel message becomes all the more clear. It also makes the parables a little more exciting, more revolutionary, more prophetic, to know that they speak to real world issues of justice and are not just spiritual allegories.

Labels: theology

At 8/13/2007 11:05:00 AM, Derek Berner

I've felt this way about certain parables for a long time. I know in several cases I've read it, gone "...what?", asked for elucidation and received an interpretation through the evangelical lens, and was left understandably unfulfilled intellectually.

I know the shrewd manager parable confused me for a long time, and I rationalized it by reading in that he was telling the serfs to immediately pay off part of the debt so as not to be burdened, as the manager learned from his mistake of being careless. Which doesn't actually fit that well with Christ's summary of the parable's message.

I remember in high school being told that the only way to read the Bible is literally and that any form of contextualisation is wrong except in extreme cases where it is needed to harmonize apparently contradictory passages. I remember thinking, but the bible was WRITTEN in a specific context! How can one possibly say that any piece of literature let alone the Bible was just meant to be taken as 100% scientific-historical-spiritual-religious fact at face value? I mean, the creation story as written definitely is more of a fable than a factual account, and the story of Job probably never happened but that doesn't discount the relevance of either.

And saying that clearly allegorical passages like Jesus' parables HAVE to be interpreted through the evangelical lens really speaks volumes about the evangelical community. It's like saying, OK, yes, some parts are open to interpretation, but we've figured that out for you so you don't have to.

I think I like the lens analogy actually, though more in the sense of a telescope lens than an eyeglass or microscope lens since we're really looking into the distant past. It's kind of like looking at Mars and trying to discern stuff, and though your observations you become convinced that there are channels built by an advanced civilization, only to find out that your lens wasn't perfect and when you switch lenses those channels aren't actually there.

Though that would suggest that to get the most accurate reading one would have to try many different lenses.

At 8/13/2007 12:02:00 PM, Derek Berner

I was always taught that the parable of the Good Samaritan was an allegory for the Christian Gospel. Christ was the unfortunate stranger, the bandits who robbed him and left him for dead was the sinful world who crucified him, the Priest and the Levite were his own people who rejected him, and the Samaritan was the gentiles who ultimately accepted him. His beating and subsequent recovery were his crucifixion and resurrection.

However, I always thought this interpretation was a lot of hooey and it was designed to purposefully avoid the obvious, direct meaning: that the person who inherits the Kingdom is the person that reaches out to people and earnestly cares for the needy and afflicted, not the person who belongs to a specific club. The fact that the religious majority not only shunned, but really hated these people makes me wonder if Jesus would have talked about "the good atheist" or "the good homosexual" in modern times.

At 8/13/2007 03:48:00 PM, inthedr

What a twisted way of interpreting scripture - especially Matthew 25 (parable of the talents). The message throughout the gospels is that God loves the fruitful life (Matt 13, John 15, the cursing of the barren fig tree). In fact, the whole Bible depicts this. In terms of the ruler being evil and unkind, haven't you read Revelation 19 or Isaiah 63 in reference to Christ when He returns to establish His kingdom on the earth: "Who is this coming from Edom, from Bozrah, with his garments stained crimson? Who is this, robed in splendor, striding forward in the greatness of his strength? It is I, speaking in righteousness, mighty to save. Why are your garments red, like those of one treading the winepress? I have trodden the winepress alone; from the nations no one was with me. I trampled them in my anger and trod them down in my wrath; their blood spattered my garments, and I stained all my clothing."

Remember, He came as a Lamb, but is returning as a Lion.

At 8/13/2007 03:53:00 PM, Mike Clawson

I may be confusing my early church fathers, but that allegorical reading of the Good Samaritan was first suggested, I think, by St. Augustine.

Of course that allegorical reading totally ignores the fact that Jesus used the story to answer a very specific question: who is my neighbor?

And the astonishing thing is that Jesus turns things around and says "The ones you are failing to act like neighbors towards, are sometimes the very ones who are acting like neighbors towards you. They get it, and you don't."

I think Jesus absolutely would talk about the "good atheist" or the "good homosexual" these days. He'd say to us Christians "Some of these people are doing a better job of following me than you folks are."

When I was a youth pastor I used to have the kids take this parable and reinterpret it into some other imaginative setting (e.g. modern day, mobster scene, sci-fi, high school cliques, deep South, etc.) and it was always interesting to how they re-cast the characters. Most of them did a great job of choosing a "Samaritan" that really did capture the spirit of the story.

At 8/13/2007 11:45:00 PM, Mike Clawson

Paul, can you please explain to me why (according to your interpretations) Jesus says one thing but does another? Why would Jesus tell us to "love our enemies" and to be peacemakers, but then turn around and do exactly the opposite himself? Is the way of Christ a way of peace or not? Did he mean what he said or not? I'm sorry, but your interpretations seem to make Jesus out to be a liar (or else what these days we'd call a "flip-flopper").

I also notice that the passage you mention in Revelation 19 also describes Jesus with a sword COMING OUT OF HIS MOUTH! (v. 15) Something about that suggests to me that maybe, just maybe, we should read this passage symbolically.

Hey Mike,

Can you please interpret Isaiah 63:1-2 for me? Also, please address Jude 14-15. Why don't we also look at 2 Thessalonians 2:10-11 (I remember speaking to another Christian he could not believe this was in the Bible because it didn't mesh with his concept of God). But it appears "God shall send them strong delusion that they should believe a lie..." Please explain for me.

God is just, as well as merciful.

When the time comes for Jesus' return (coinciding with something called the "great tribulation") there will be judgment executed upon the earth, hence what you read in the parable you referenced.

Your stretching of scripture is what Peter referred to here in reference to what people were doing with Paul's letters: "...in which are some things hard to be understood, which they that are unlearned and unstable wrest (twist), as they do also the other scriptures, unto their own destruction." (2 Pet 3:16).

I mean no offense or disrespect (hey, this is your blog), but this type of twisting is hard to take seriously, if I didn't notice that some people actually agree with you. Wow.

Mike, straining the scripture through a political and temporal framework is a bad thing. Especially when that framework emerges from a political philosophy that debases Christian thought, defames the Majesty of Christ and has been the greatest idealogical source of social strife in the history of the world.

At 8/14/2007 06:07:00 PM, Mike Clawson

Paul, what you call "twisting" I call good hermeneutics. In fact, I mean no offense, but actually tend to find your style of biblical hermeneutics rather twisted and disrespectful to the biblical texts. (Not that I at all think that you are intending to be disrespectful. I just think you're mistakenly reading them in a way that actually does violence to their original intent.)

At any rate, is there any reason to suppose that your interpretive assumptions and methods are actually more correct than my own? Why should we assume that your interpretation of these parables is correct and mine is twisted? Why couldn't it be the other way around?

At 8/14/2007 06:15:00 PM, Derek Berner

Garet, you're committing the logical fallacy of poisoning the well. You're arguing that because Karl Marx espoused this style of exegesis, and Karl Marx was bad, that the exegesis is bad. Karl Marx breathed air. Is air bad?

You have to consider arguments at face value, not reject them because of their source. If Hitler told you a kid was drowning, and it turned out to be true, would you let the kid drown because Hitler told you?

And finally, how can people assert in good faith that their exegesis is a literal reading and all others are interpretations designed to promote a liberal agenda? Honest question!

At 8/14/2007 06:20:00 PM, Mike Clawson

"Mike, straining the scripture through a political and temporal framework is a bad thing."

Unless that framework is already inherent in the text.

I'm not suggesting that we should read scripture through a Marxist lens (you were the one who brought that up), but I think the lens of justice and liberation for God's people is unavoidable. This is a dominant theme in scripture from Exodus, through the prophets and the Babylonian exile, and of course all the way through the New Testament. Surely you're aware that passages like Exodus 3:7-10 and Luke 4:18-19 central to what the whole story of the Bible has been about?

I mean, I'm preaching on the Last Supper this week, and the connections between God's liberation of Israel at Passover and Christ's liberation of all humanity through the New Covenant are unmistakable. The whole story has been about liberation - and true liberation encompasses all aspects existence: political, temporal, and spiritual. We should resist the gnostic tendency to over-spiritualize Christ's message to the point where it has been reduced to only liberating us from personal, private sins and ignores our need to be liberated from larger, societal sins as well (i.e. the need for justice).

Listen, either God is the God of all of existence or he is not. Aren't political and temporal realities still a part of God's total reality? Aren't they just as much a part of his mission of reconciliation in the world? Or has God compartmentalized his kingdom and said "Well, I'll reign over the spiritual and the personal and the private, but I'll just leave politics and society alone?"

Somehow that second option doesn't seem like the God I encounter in scripture.

Couldn't resist as I just read this this morning: Matthew 22 and the parable of the Wedding Feast. I would highly recommend you read it and then interpret who is who.

Who is the king in verse 2 (must be God of course)? Who is the son, if not Jesus?

And look what verse 7 says (strikingly similar to the parable you referenced in Luke): "But when the king heard thereof, he was wroth: and he sent forth his armies, and destroyed those murderers, and burned up their city."

Could this be really be God? Absolutely.

Please stop trying to be overly creative in your interpreting... you're on a slippery slope.

At 8/16/2007 11:16:00 PM, Mike Clawson

Paul,

I'll let my friend Sarah Dylan Breuer, who is much more studied and a far better exegete than I, address this particular parable you mention. On her lectionary blog regarding this parable she writes:

"This Sunday's gospel passage is a challenging one. Like last week's gospel, it tells a story of violence that should disturb us. Like last week's gospel, it portrays the devastating consequences of perpetuating or escalating the spiral of violence rather than choosing Jesus' way of resisting evil with love rather than arms and blows. Like last week's gospel, it seems to invite an allegorical reading, with the king as God, the king's son as Jesus, and the unworthy subjects who kill the king's messengers as those who persecuted and killed prophets, and especially those who persecuted and killed Jesus and his apostles.

Once again, though, I'm mostly resisting that ready temptation to allegorize. Jesus' condemnation of violent retaliation is so clear and so consistent, not only in his teaching throughout his career but also and perhaps even more importantly by his own example of becoming subject to death on a cross rather than striking out at his persecutors, that I think one would need a great deal of evidence to support a suggestion that the God whom Jesus proclaimed is one who will retaliate violently when God's messengers are attacked. Whatever else we might want to say about this passage, let us remain always grounded in the central confession of Christian faith that we believe that Jesus is God Incarnate, and if we believe that, we must say that the eternal character of God is the character displayed in Jesus, who is nothing like the vengeful king of this story."

She goes on to acknowledge that many people will still want to interpret it allegorically, and gives advice for how to preach the passage according to that interpretation too. Anyhow, you may still disagree with her interpretation of it, but I hope you can appreciate the fact that it is based solidly, as she states clearly in the portion I quoted, on a theology of the incarnation and on a theology of the Cross.

I hope you can recognize how such a reading is based not on "Marxism" or some attempt to twist the scriptures, but on trying to reconcile the scriptures to themselves, and to what we hold to be most central to our faith - namely God in the flesh crucified for our sins without thought of vengeance or retaliation.

Last comment on this post - promise:)

So who is the king referenced in this parable? Who is the Son? What is the context?

What did Paul mean in Romans 3:5b-6 "Is God unrighteous who takes vengeance? (I speak as a man) God forbid: for then how shall God judge the world?"

He also says that we are not to take vengeance into our own hands because the Lord says, "Vengeance is mine - I will repay."

I'm not trying to cast God in the light of a sadist, but to make it very clear to you that God is just (not only merciful) and those who reject Him outright will suffer the consequences.

You haven't reconciled even ONE of the scriptures I've mentioned above (in other posts) which paint a much clearer picture than your poor interpretation of this parable.

My fear is that (perhaps unknowingly) the blind are leading the blind here - and we both should know where that leads.

Wow ... me and +Tom Wright -- you're placing me in very distinguished company! Glad you find the lectionary blog so helpful, and many thanks for your own ministry and wrestling with these texts.

And as for my interpretive framework being Marxist, I'm reminded of an episode of the BBC series The Vicar of Dibley, in which a 'Tory' (political conservative) parishioner upset with the sermon asks the priest, "And just where did you get that Communist claptrap you were preaching on Sunday anyway." "The Sermon on the Mount," the priest replies.

A line of argument that says, "This sermon talks about economic justice; Marxist liberation theologians of the 1970s talked about economic justice; therefore the sermon is Marxist" is pretty poor reasoning; and more importantly, by that standard, Jesus of Nazareth, St. Paul, Micah, Amos, and Isaiah (to name a few) were all Marxists as well. Pretty good company to stand in, I think, though I share a birthday with Karl Marx (as well as Soren Kirkegaard and Ann B. Davis, who played "Alice" in The Brady Bunch) and not much else.

Blessings, and thanks again for your kind and very encouraging words.

At 8/19/2007 11:50:00 AM, Derek Berner

Paul, you're asking leading questions about the parable. By asking those kinds of questions, you force the answerer to try and allegorize, when Mike has made it clear that he's trying not to auto-allegorize every parable that comes out of Jesus' mouth.

To use a previously-quoted analogy, what you seem to be doing is holding up a couple of puzzle pieces and demanding to know exactly where they go, refusing to let anyone work on other parts of the puzzle until your pieces have been placed, and then refusing to let people move the pieces once they are put down.

I'm by no means a biblical scholar, but I can appreciate there are parts that are really difficult to reconcile, and I get sick of people insisting that their reading is THE reading and everybody needs to stop thinking about it and listen to them.

At 8/19/2007 03:05:00 PM, Mike Clawson

Thanks for dropping by Sarah! As you can tell, I'm a huge fan of your lectionary blog!

And Derek, you've hit it right on. Paul asked who the king is, who the son is? They're a king and his son, period. Why allegorize it?

We have remember that even though to us stories about kings and princes seem like otherworldly fairy tales, in Jesus day these were everyday political realities. A king, to Jesus' listeners, was not a character from a kids story like they are today. A king was an immediate political force in their lives - someone who was taxing and oppressing them (e.g. Herod).

Jesus telling them a story about a king who gets back at a few murderers by burning an entire city would be like Jesus telling us a story these days about a President who retaliates against an act of terrorism by a handful of people by launching a full scale war against an entire nation... if Jesus told us a story like that, would we automatically think he was intending for us to allegorize it, or would we think that he was offering a direct commentary on our present political situation?

At 8/21/2007 02:48:00 PM, Steven Carr

In Luke 19, Jesus answers people who thought the kingdom was coming straight away.

Just before Jesus dies and returns after 3 days, Jesus tells them of a nobleman who goes away to a distant country, only to return as a king.

Just before Jesus is killed by the Jews, he tells of a man who is rejected by his countrymen, but returns with the power to judge them.

Perhaps the king in Luke 19 is meant to be Jesus....

At 8/21/2007 03:18:00 PM, Steven Carr

'Here we are presented with a harsh and violent ruler who leaves his country to be crowned king by the emperor, but whose citizens also send a delegation to ask that he not be made king because of his cruelty (an obvious reference to the real history of Herod Archelaus from Jesus' childhood).'

'Obvious'? And what emperor in the parable? I see no emperor mentioned. Has Mike made another of his breakthroughs in Biblical studies.

Herod Archelaeus was never made king in a distant land. In fact, Augustus refused to make him a king. Luke correctly never refers to him as a king.

The nobleman in the story was made a king.

And Archaleus had the power to have people killed *before* he went to Rome. The nobleman in the story did not.

The parallels are uncanny!

Especially the reference to the emperor, the one that Mike writes about and who is never mentioned in the parable.

Herod Archaeleus went to a distant country to see the emperor just like the nobleman in the parable didn't see any emperor. Clearly then the parable refers to Herod Archaleus.

At 8/21/2007 03:23:00 PM, Steven Carr

MIKE

'...but whose citizens also send a delegation to ask that he not be made king because of his cruelty.'

CARR

I can't find where that is given as the reason why they ask that he not be made king.

Mike must be using a later edition of the Bible, or he is adding elements not found in the text - mention of an emperor, mention of the nobleman's cruelty as the reason why the delegation did not want Jesus (sorry, the nobleman) to rule over them.

But why would Mike add elements to the parable which are not there, but are present in the story of Herod Archaleus?

I'm totally baffled!

At 8/22/2007 12:39:00 AM, Steven Carr

DEREK

'Garet, you're committing the logical fallacy of poisoning the well. You're arguing that because Karl Marx espoused this style of exegesis, and Karl Marx was bad, that the exegesis is bad. Karl Marx breathed air. Is air bad?

You have to consider arguments at face value, not reject them because of their source.

CARR

Unable to attack my analysis of Luke 19, Mike attacks the source.

He will be claiming I am a Marxist next...

I should point out that that would be as untrue as claims that Luke 19 mentions that the nobleman met an emperor or that the text says people did not want to rule over him because of his cruelty or that Herod Archelaeus was a king.

At 8/22/2007 02:34:00 PM, Mike Clawson

On another blog you said:

"I know I am smarter than almost all other people. This is just a fact. There are some people smarter than me though - Stephen Hawking for example."

...and then you wonder why people aren't that interested in "dialoguing" with you?

(Especially when your definition of "dialogue" appears to be "pointing out why they are wrong".)

At 8/22/2007 03:09:00 PM, Steven Carr

I was asked a question.

It just happens to be a fact that people who win scholarships at Cambridge, despite an extremely deprived background, and get a first class degree while there are smarter than most other people.

Sorry if I answered a question honestly.

Mike is willing to post about me, but has expressed that he will not discuss any arguments I put forward.

I wonder why. Perhaps because I point out where he claims that the king in Luke 19 refers to somebody who in reality was never made king.

I listen carefully to Mike , and check out what he says.

No wonder I am an unwelcome guest.

Dude, as if you were not aware, this is Liberation Theology. It proceeds from viewing scripture through the framework of Marxist theory. It may seem avant-garde, but it is old hat.

Can I recommend Nancy Pearcy's Total Truth?